Surviving My Daughter’s Stillbirth

In this profoundly moving essay, one mother shares the story of her daughter, Tegan, who was stillborn at six months. Through moments of humor, despair, and raw honesty, she explains her need to find words where there are none, and reveals the quiet resilience needed to carry on in a family forever changed by loss.

- Written By

- K.K Glick

How are you? Pretty common question. Generally not considered too painful or prying. For me, the friendly greeting is a tiny assault peppered throughout my day. Like a violent gust of wind, I’m left off-kilter, momentarily blinded with a farkakte hair part. It’s been almost two years, and I’m still flummoxed and flailing when asked how I am since the death of our baby at six months pregnant. Since her stillbirth.

My father would get the question constantly. How you doing, John! A hazard of his daily battle with Parkinson’s, cancer, and a weak (but mighty) heart. Pretty good, how’s about you? he’d reply, every time. He couldn’t stand from a chair, walk, swallow efficiently and all five words left him winded, but he meant it. He was good! I’m forever my father’s daughter but lacking his Boomer aversion to negativity and neuroses. "Cup’s half empty" has proudly always been my Xennial mantra.

"Right after her birth/death, I actually didn’t hear it much. Everyone knew how I was."

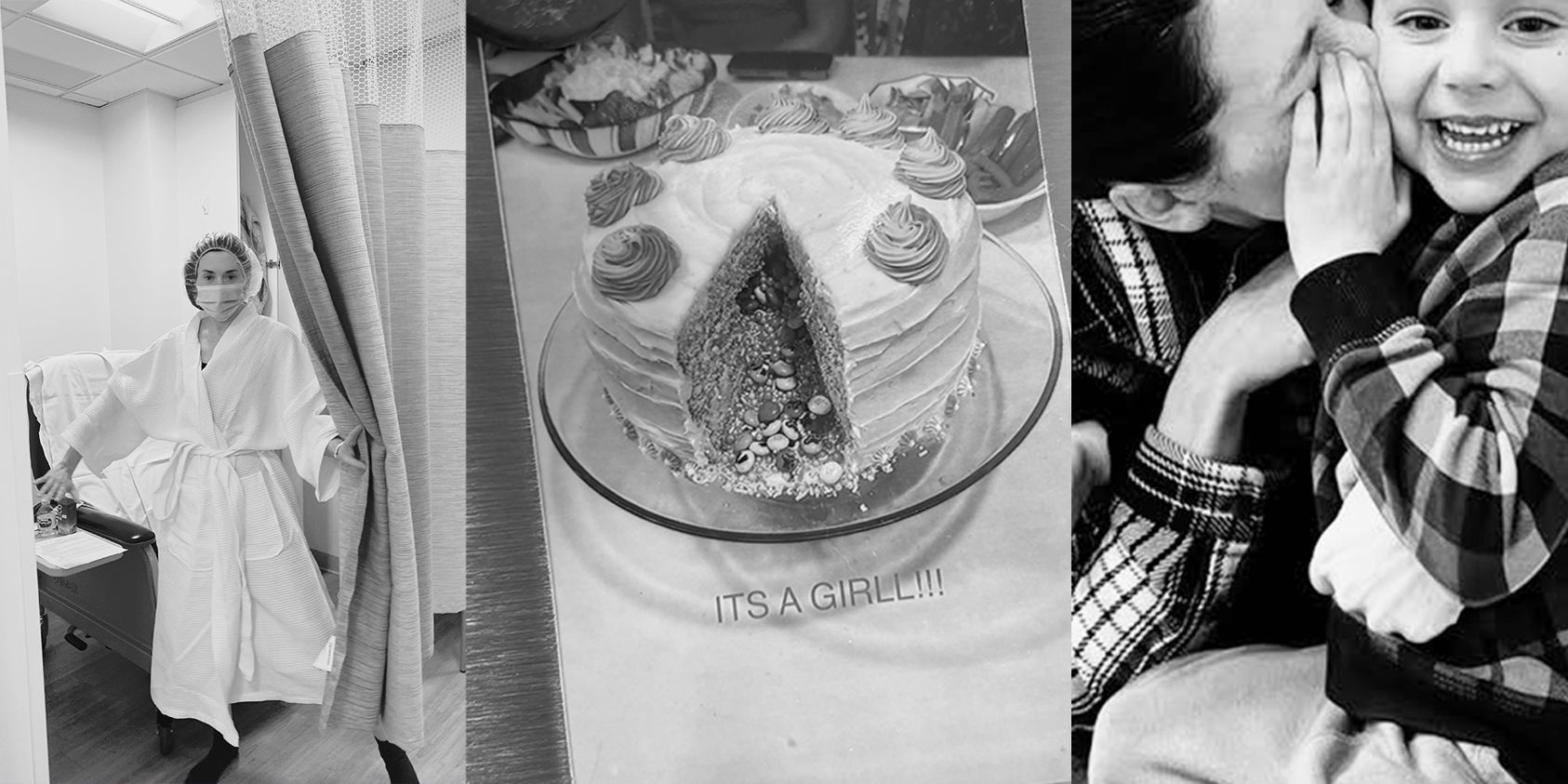

Right after her birth/death, I actually didn’t hear it much. Everyone knew how I was. My husband, cousin, and our then four-year-old son and I navigated those first days home from the hospital. We found space for the flowers and penne alla vodka, and, in an epically surreal and shame filled about-face, broached the formidable task of telling people our bad news after we had just told people our good news.

I’d leave the house no longer trying to conceal the growing bump under my coat but now, the lack of one. The How are you? was landing as if someone had asked for directions in another language.

“Hey. How are you doing?”

“Um. Wait, what? (squinting) Sorry. I can’t help you with that.” Puzzling; how would I possibly know this?

By Spring, I’d rehearse answers. With clammy hands, I’d brace for knowing eye contact and warm inquiries into my well-being. Hangin’ in was a solid go-to, always making sure to drop the “g” to feign breeziness. Summer came and with it, I’m all baby weight and no baby. Though loved ones were genuinely wondering about my well-being, I couldn’t gauge where constantly organizing her clothes, yelling, fits of escaping to my basement in a rage to throw things but also being the most present with my son since his birth placed me on the good-or-bad scale. That Fall, I gave a Good! to another Mom that was so pitchy and tragic I almost collapsed in laughter right there on the playground wood chips. How tempting to release the pent-up energy it took to look back at someone and try to tell them, or try not to tell them, how I was. Because, just how and where, praytell, do I start?

"How tempting to release the pent-up energy, right there on the playground wood chips to try to tell them how I was. Because, just how and where, praytell, do I start?"

Do I start with the seven IVF egg retrieval cycles we slogged through over two years to get to this pregnancy?

My son’s first birthday was quickly followed with a pandemic and my father’s death. We decide that "Life. Its ‘circle of’ is what we need.” Our next baby was hope. Visions of Eli’s younger buddy lived rent free in our heads. We did a Frozen Embryo Transfer with the only embryo we had left. We giggled at my nausea as I left for the pregnancy test uptown. I changed my passwords to my Dad’s name, this one’s namesake since I knew I was destined for boys. I skipped off the 1 train eager to check my phone. Weird - the nurse hadn’t left a voicemail yet with results. Why hadn’t the nurse left the voicemail? I reached the West Side Highway and understood. I was not pregnant. My dad died again that day.

Sadly, IVF is commonplace, which may be why it’s too often perceived as something one casually just “does.” Like your taxes or the Magic Kingdom. Do IVF, get a baby. Fin.

"What’s not accurately communicated is the failures and mainly, the emotional beating you’re left with from the months-long daily dogfight that comes with these treatments. And the real kicker - waiting."

What’s not accurately communicated is the failures and mainly, the emotional beating you’re left with from a months-long daily dogfight. And the real kicker - waiting. Shots are easy, but waiting and wondering what your life will be, who you’ll be Mother to, waiting on hold to plead with insurance again, waiting to see if your posture will ever release the shame it holds from having to resort to this while seemingly surrounded by women who pirouette into pregnancy is what takes the often undisclosed toll.

We did the dogfight all over again. Three times. With not one viable embryo to show for it. Half a year and thousands of dollars gone, and we hadn’t even made it to a pregnancy test. I looked like The Scream. We took a long break, switched clinics, and I removed gluten, dairy, sugar and caffeine from my diet. Fun! But, it worked and I became pregnant after several more IVF cycles. WAIT, THIS IS TOO MUCH SCIENCE; what’s this woman going on about? I’ve lost you. Eyes tend to glaze over when one gets too deep in the brass tacks of fertility treatment speak. I’ll stop.

"I’ve lost you. Eyes tend to glaze over when one gets too deep in the brass tacks of fertility treatment speak. I’ll stop."

I could tell you about the way my second wonderful doctor placed her hand on my right shoulder as my own first wonderful doctor, who’d brought Second into the examining room for reinforcement (it takes a village) told me that she could no longer detect a heartbeat. At six months pregnant. Was it my shoulder or my shin? If I could tell you the time spent at traffic lights pondering shoulder or shin.

Or how, after a petrifying first trimester of tests with normal results to our blissful awe, that eventually I couldn’t zip my coat over my bump and had to start telling people our good news. And how, I’d repeatedly tell those ecstatic to hear I was finally pregnant to simmer down; I’d consider this pregnancy real when it was time for the gross drink which tests for gestational diabetes. Wink. And how the drink was already in my kitchen cabinet for my next appointment when I stopped feeling her move. (Too much? Too maudlin? Whiny! At least you have the one!)

I’ll tell you about the nurses. We’re nothing without our nurses. Nurse Anne: roughly 6’4”, born in Ireland who walked as if en route to deliver an emergency freshly baked loaf. “We’ve been waiting for you,” she said, sans pity, in her waning brogue. Nurse Maddie: young, quiet, slight with fine brown hair all belying a keen inner sturdiness. She wore pale blue Hoka’s and, thank all the gods, was not a talker. She nursed us as steadily at bedtime when the surreal was quiet and dim as she did at dawn when things were suddenly fluorescent and very loud. I demanded the epidural way too late thinking our two pound girl wouldn’t cause me pain. Big mistake. Huge.

And lastly, Nurse Carrie who, I realize now, is not of human descent but of the Clarence Odbody species. She relieved Maddie at dawn and nineteen minutes later, Tegan was born. An angel of the chatty origin, Carrie helped deliver then bathe our sleeping daughter, wrapped her in hand crocheted yellow blankets, cried and laughed with us, completed Tegan’s birth and death certificate. She was by our side up until Jed and I left Mount Sinai that February evening two entirely changed people, then returned to her spaceship and beamed herself to one of the other 20,999 stillbirths that occurred in this country last year. I’ve never told anyone about the nurses.

I’ll tell you about Mrs. Z, a preschool teacher of Eli’s at the time. An old soul with Audrey Hepburn frame and unfussy brown bob, she and her joie de vivre were incapable of typical teacher formality. “I cannot not hug this boy,” she’d say in her thick Albanian accent whisking him out of the car each morning. She played the flute on each child’s birthday. I adored her. The morning I returned to drop-off, my whole body trembled about to reunite with her and the other women who had felt my growing belly and counted down to Eli’s little sisters’ arrival. Before I could brake on that raw March morning, Mrs. Z climbed in the passenger seat next to me, gripped my shoulders and through steady tears said, “Me too. Same time.”

"I could hold sermons about the love that embraced our family."

I could hold sermons about the love that embraced our family. After moving here, I quickly discovered the intimacy that comes when a group of women find themselves raising children next to each other. A pride of lions zoned for the same school district. Word spread and the lionesses swooped in. For two weeks, we were fed. New Jersey’s best chicken parm, bales of arugula, tiny Tupperwares of homemade salad dressing, bagels from Goldberg’s (never Noah’s), mini cupcakes and organic lollipops for Eli. Weekly fresh berries. Overflowing bags from Root Steakhouse. Thick warm socks, blankets, a handle of Casamigos, monster trucks from bosses and neighbors. It was endless. Sometimes before bed I still peek at the handwritten schedule of meals by my closest lion, fluent in loss. The slant of her S's in Sheetpan Butternut Squash Gnocchi wil lull me to sleep. And when a “T” and “E” bracelet that doesn’t come off broke last Christmas morning leaving me unhinged, my sisters college roommate sent two more. Best to have a backup.

I can’t tell you what it’s been like watching a now almost six year old as her void cemented in our home. I can just share text messages sent to my sisters since she died:

Eli just asked if we can name his next sister Tilly.

A nanny just asked us when I’m gonna give that boy a sibling! Lol!

E just told Oscar’s mom that his sister died in my belly so he hates leaving playdates.

Eli just asked our waitress if she was Ariana Grande.

There’s more, but I’ll spare you the complicated dance of having handed your family a silver platter of grief. How sometimes placentas are the size of a silver dollar pancake. The silent standing O the front desk gave us as we left the hospital. Then fighting my knee-jerk reaction to say, “So sweet. Congratulations. Is yours alive?” to the woman holding her newborn in the elevator. Gripping Tegan’s mini urn in my pocket at Christmas Eve mass petrified I’d faint from the incense. A chemical pregnancy last August. The fitness that grief demands of a marriage. But, it’s enough already. Dead babies don’t land, and “stillbirth” is a word people prefer tucked away. Confirmed when, at a Perinatal Loss Symposium, a pathologist shared how he could count on one hand the professionals properly trained in reading a stillbirth placental report in our country. Because, as he was told early in his career, “There’s no money in dead babies.”

"So now, nearing the second anniversary of Tegan’s death, my grief, fury and jokes are for a select few. And every day, surrounded by children with siblings to spare, you take the pain and push it down to your feet."

So now, nearing the second anniversary of Tegan’s death, my grief, fury and jokes are for a select few. And every day, surrounded by children with siblings to spare, you take the pain and push it down to your feet. Then cry in the car outside Dunkin. And, later at dinner with the lions. While laughing. Always praying the anger doesn’t end you. I didn’t know pain takes practice. Don’t cry for us. Like my Dad, I’m pretty good! And it’s alone in my kitchen, chopping vegetables for dinner when I allow myself to to get lost in what might have been-

Chop, chop, chop-

Who was she, who was she, who was she.

What would she sound like -

Would her hair curl, her hair, her hair,

Her brother, her brother, her brother.

Eli and I left his school on a sunny, warm day last Spring. We planned to get a croissant after I timed his running jump to the stone bench flanked by hydrangeas. We passed a Mom who I’d only met once, but liked. Eli and her brood of three played as we moseyed to our cars. After swearing we’d grab that coffee she turned back and asked, “Is Eli your only child?”

K.K Glick

K.K Glick is an actor and writer, based in New Jersey. She lives with her husband, son and two dogs, Gus & Morty.