Parenting

Alexa von Tobel's Tips For Talking To Your Kids About Money

Alexa von Tobel is a force. The Harvard-educated mother of three is the Managing Partner of Inspired Capital, a venture capital firm she founded earlier this year. She is the founder and former CEO of LearnVest, which she started at the age of only twenty-four and the New York Times-Bestselling Author of "Financially Fearless" and "Financially Forward." She also managed to show up at our office for this interview looking flawless in a white suit which, given her three children four and under, struck us as quite impressive. Alexa has dedicated her career to making personal finance something everyone can understand. Here, she turns her expertise on the most important things for parents to consider when talking to their children about money.

- Photography

- @shoptheinside

- Interview By

- Liz McDaniel

- Illustration

- Kath Nash

Keep It Tangible

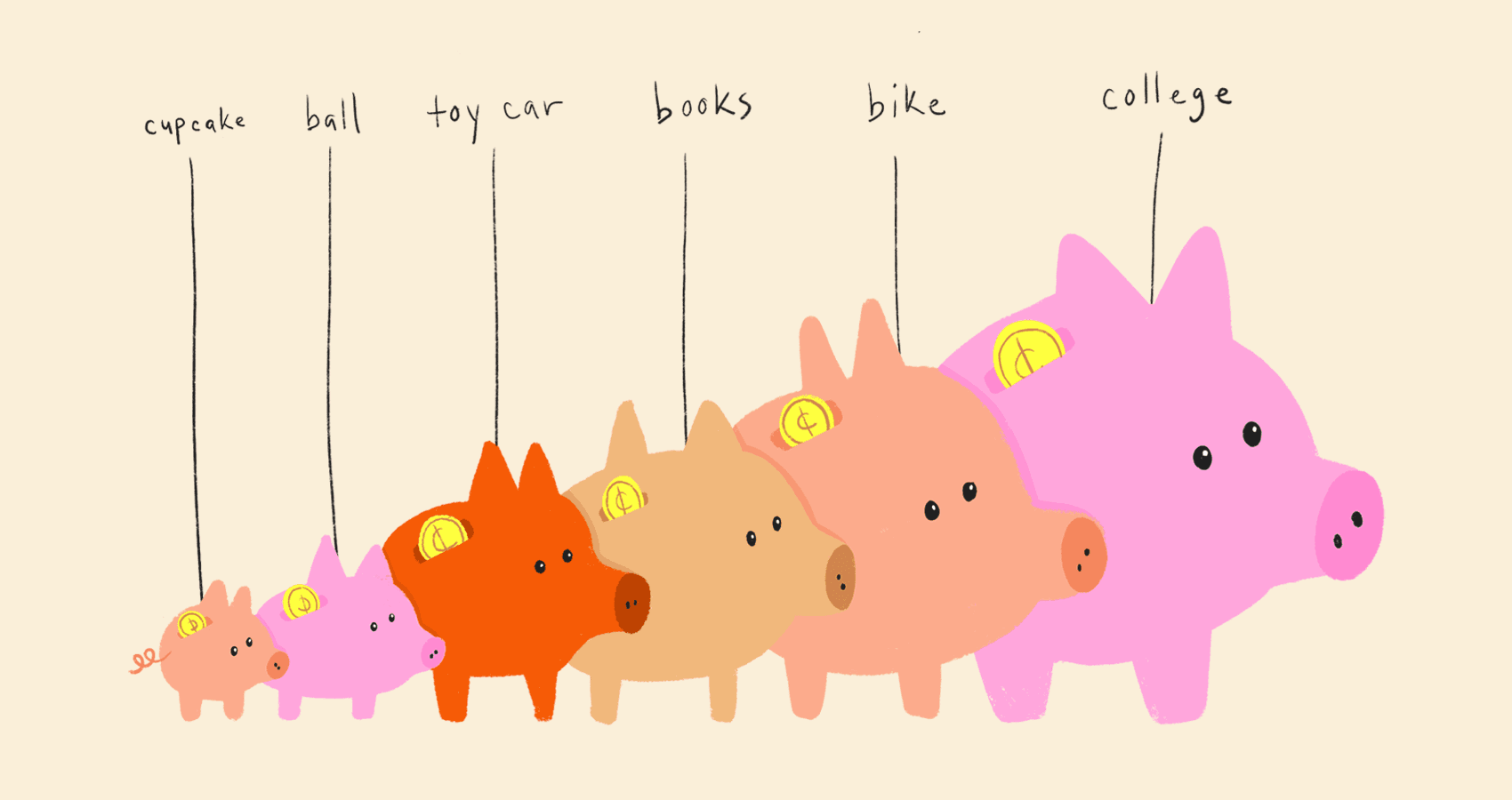

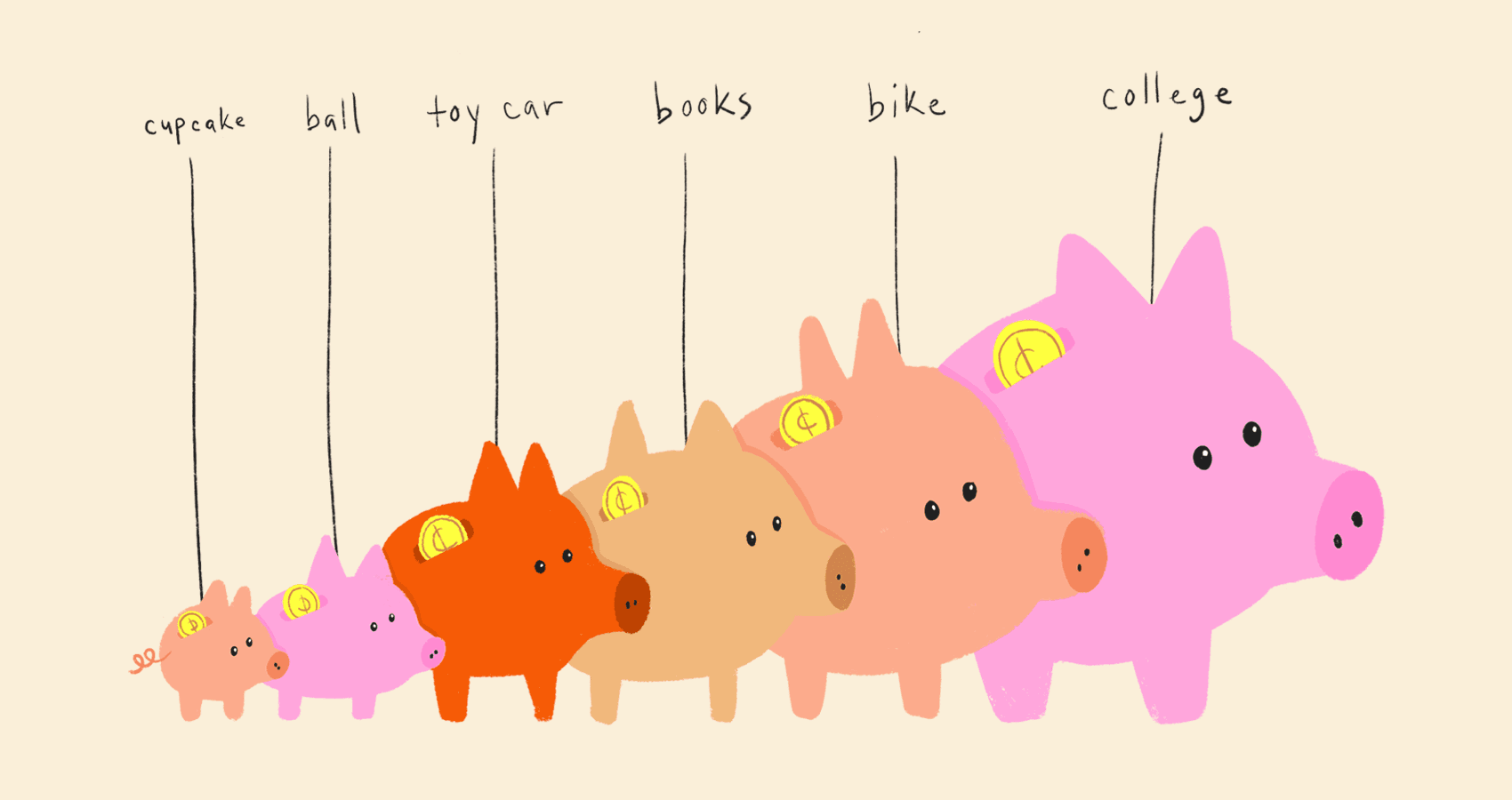

The most important thing when you’re teaching little kids about money is to make it tangible. My daughter, Toby, who is 4.5, has six piggy banks. There’s a really big one that’s the size of two footballs, all the way down to a really tiny one that’s the size of a tennis ball. The big one is for college, so far out in the future, and the little one is for something she wants within the month, like a cupcake. And every time we give her a bit of allowance, we actually give her pennies, quarters and dimes. We make it really physical. What we’re trying to do is not only connect to the core of delayed gratification but to the feeling that this is money and you need to save it and at some point it can be used to buy something. It’s really about connecting those dots. Not to mention the fact that you’re also teaching children math which is obviously important when it comes to money.

The most important thing when you’re teaching little kids about money is to make it tangible. My daughter, Toby, who is 4.5, has six piggy banks. There’s a really big one that’s the size of two footballs, all the way down to a really tiny one that’s the size of a tennis ball. The big one is for college, so far out in the future, and the little one is for something she wants within the month, like a cupcake. And every time we give her a bit of allowance, we actually give her pennies, quarters and dimes. We make it really physical. What we’re trying to do is not only connect to the core of delayed gratification but to the feeling that this is money and you need to save it and at some point it can be used to buy something. It’s really about connecting those dots. Not to mention the fact that you’re also teaching children math which is obviously important when it comes to money.

Be Matter Of Fact

Having studied money, knowing so much about money, it’s really important to realize that your oldest money memories tend to shape, psychologically, how you feel about money. So if you grew up in a house where you never talked about money, you tend to be more private about money. If you grew up in a household where money was incredibly stressful, then you tend to associate money with stress. But if you grew up in a household where money was very matter of fact, money is money, it’s not emotional, you tend to be better at handling money. So it’s really important when it comes to little kids to lean toward making money matter of fact. This is how much something costs. We can afford it or not. It shouldn’t be something that’s totally ignored and it shouldn’t be something that’s overly stressful, because this is what will shape your child’s attitude towards money.

Watch Your Tone

It’s hard, but it’s crucial: You have to keep the emotion out of it. A neurologist once taught me that the tone that we use when we say things, children are wired to pick up on that first. They listen to the tone that we use because they are wired to learn language and so it’s really important to keep your tone positive and constant when you’re talking about these things as opposed to getting really frustrated and angry. And, trust me, I know it’s hard as a parent sometimes. The number of times I’ve been at Target and my daughter has put 72 things in my cart! But you just look at her and say, "Silly goose, there’s no way we can take all six of these home, but let’s think about one thing that we can get." Then you go back to giving her the physical money and letting her buy something. It becomes really fun and like a game and what you’re really teaching them is strategy.

Ground It In Things They Can Understand

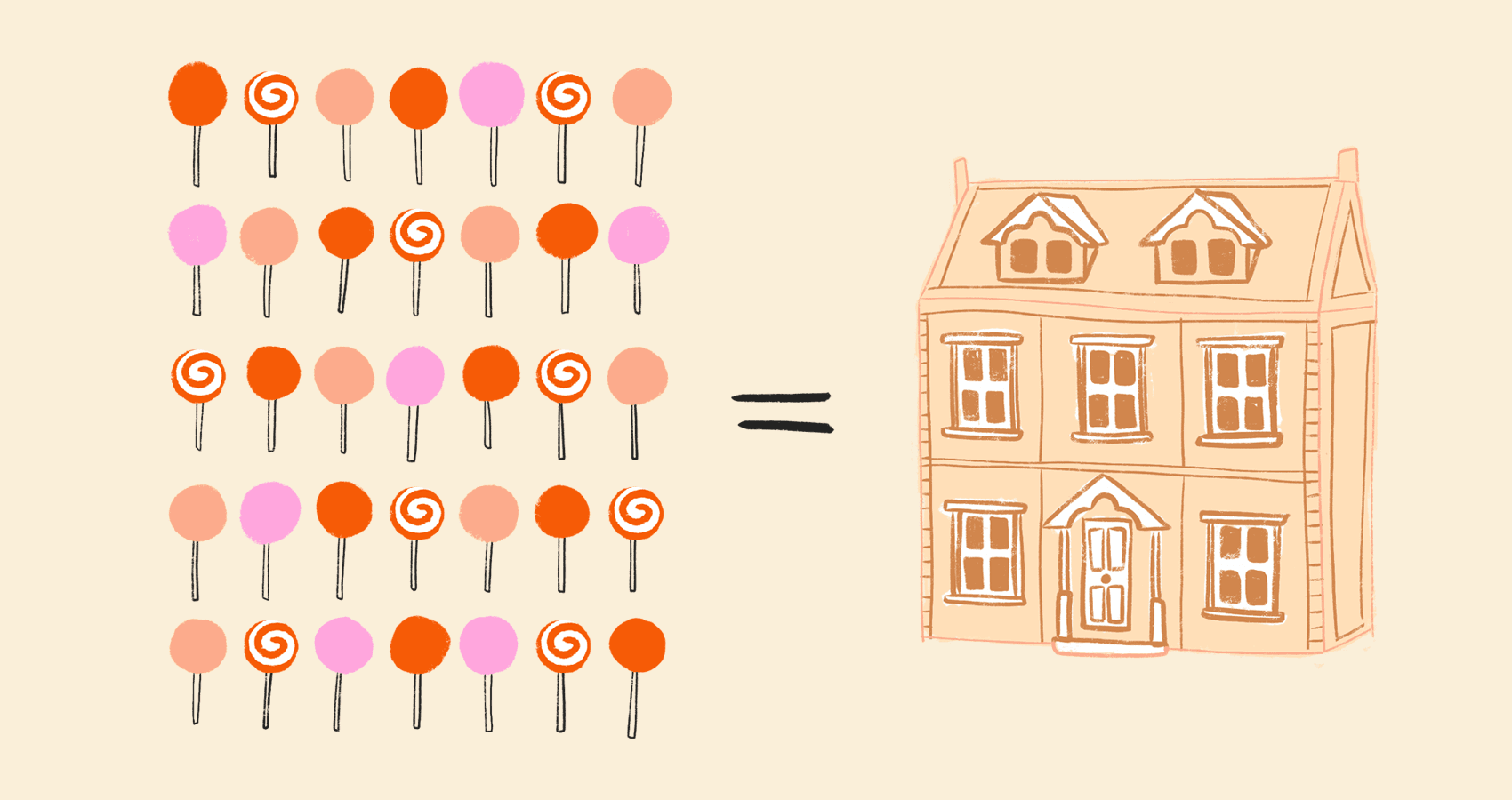

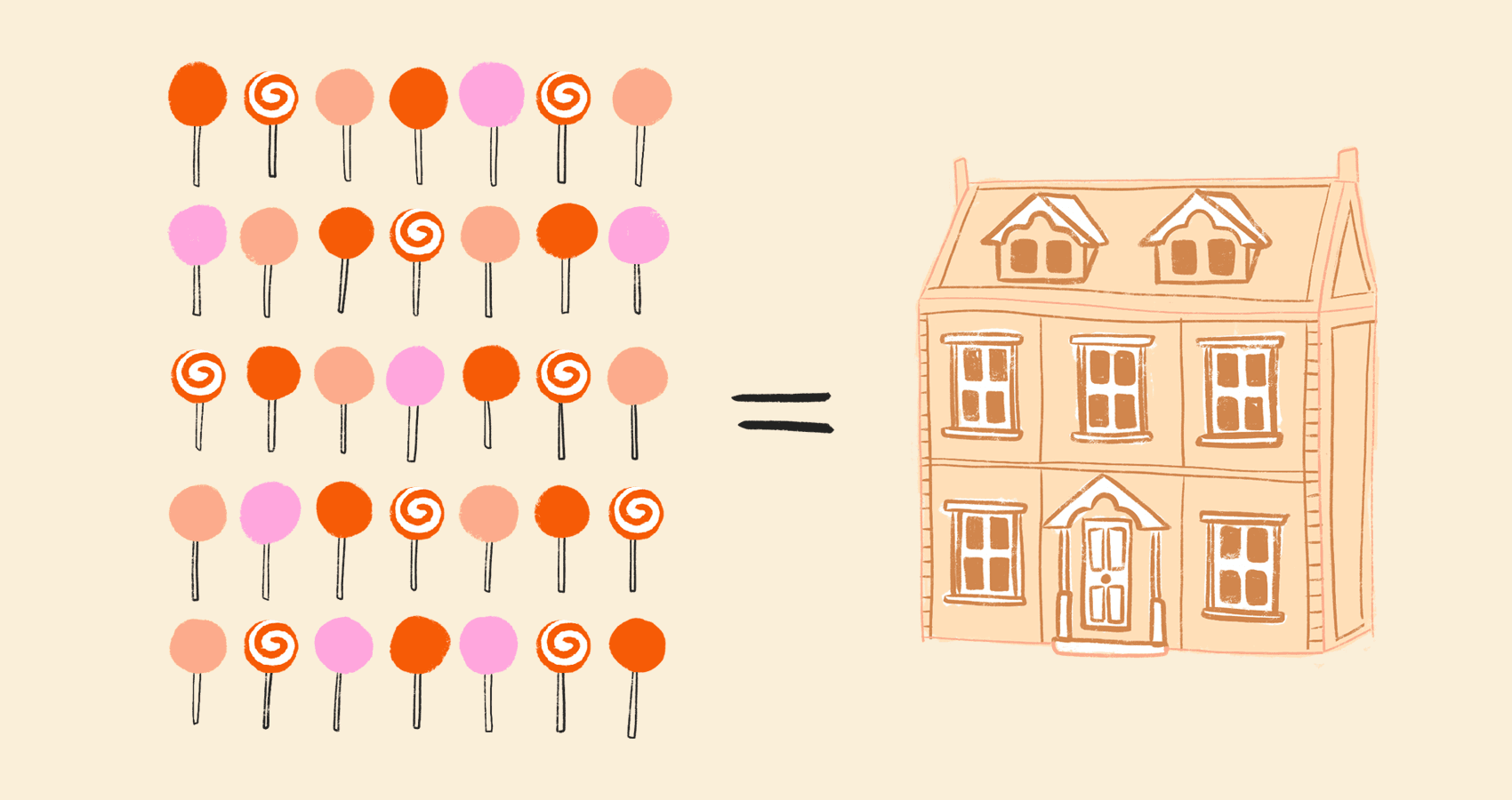

Younger kids might not understand how much something actually costs or what expensive means, so you want to try to ground the concepts in something they do understand. If a big toy for her is $40 and a medium toy is $20 and a lollipop is 25 cents, that’s how we try to talk about things. So if my daughter wanted a toy that costs $500, I’d say, “Wow, that’s 2,000 lollipops. That’s a lot, right? So that’s probably too much,” and she would get it.

It seems simple but you’re really teaching your child so many practical things. Math. Decision making. It’s about starting to get your child to recognize that they have to place their chips in one place, that they have to make the decisions and that they can’t have it all.

And when my daughter says, "But I want it all," we often bring it back to ourselves and explain that Daddy and Mommy have to make hard choices, too. That we want a lot of things and we often have to only pick one and then we have to work really hard to be able to get it. And she’s beginning to understand reason as a result. It’s really about the language we choose for our children and how we help them make good choices.

Having studied money, knowing so much about money, it’s really important to realize that your oldest money memories tend to shape, psychologically, how you feel about money. So if you grew up in a house where you never talked about money, you tend to be more private about money. If you grew up in a household where money was incredibly stressful, then you tend to associate money with stress. But if you grew up in a household where money was very matter of fact, money is money, it’s not emotional, you tend to be better at handling money. So it’s really important when it comes to little kids to lean toward making money matter of fact. This is how much something costs. We can afford it or not. It shouldn’t be something that’s totally ignored and it shouldn’t be something that’s overly stressful, because this is what will shape your child’s attitude towards money.

Watch Your Tone

It’s hard, but it’s crucial: You have to keep the emotion out of it. A neurologist once taught me that the tone that we use when we say things, children are wired to pick up on that first. They listen to the tone that we use because they are wired to learn language and so it’s really important to keep your tone positive and constant when you’re talking about these things as opposed to getting really frustrated and angry. And, trust me, I know it’s hard as a parent sometimes. The number of times I’ve been at Target and my daughter has put 72 things in my cart! But you just look at her and say, "Silly goose, there’s no way we can take all six of these home, but let’s think about one thing that we can get." Then you go back to giving her the physical money and letting her buy something. It becomes really fun and like a game and what you’re really teaching them is strategy.

Ground It In Things They Can Understand

Younger kids might not understand how much something actually costs or what expensive means, so you want to try to ground the concepts in something they do understand. If a big toy for her is $40 and a medium toy is $20 and a lollipop is 25 cents, that’s how we try to talk about things. So if my daughter wanted a toy that costs $500, I’d say, “Wow, that’s 2,000 lollipops. That’s a lot, right? So that’s probably too much,” and she would get it.

It seems simple but you’re really teaching your child so many practical things. Math. Decision making. It’s about starting to get your child to recognize that they have to place their chips in one place, that they have to make the decisions and that they can’t have it all.

And when my daughter says, "But I want it all," we often bring it back to ourselves and explain that Daddy and Mommy have to make hard choices, too. That we want a lot of things and we often have to only pick one and then we have to work really hard to be able to get it. And she’s beginning to understand reason as a result. It’s really about the language we choose for our children and how we help them make good choices.

Make It Fun

We give our daughter an allowance for above and beyond chores. The other night she cleaned up and took the trash down the hall, which is above and beyond for a 4.5-year-old. So I said, "You just earned a dime and a quarter." And what was so cute was she asked if we could make a piggy bank just for her chore money. So I decided we would make a new piggy bank and let her decorate it that weekend. You want to lean on what your child gets excited about. Try to make it fun for them to learn the basics. Make it fun for them when you spend it. Make it fun when you exhaust the piggy bank. That’s when we’re going to take her to the bank and let her physically see the money and buy something and continue to connect those dots.

Fake It 'Til You Make It

With math, that is. Tremendous studies show that the way parents talk about math is so important. If parents say, "Ugh, I was never good at math, I didn’t like it,” their children will follow suit. You have to fake it 'til you make it because if children are led to believe that these basics are hard, then you are teaching them that it’s hard, that it’s supposed to be hard. But math is not that hard. The basics are not hard. Money is not hard. If you tell your children, "Mommy loves dealing with money, money is so interesting," you totally reorient the way that they think about learning it themselves.

It’s Never Too Late

Money is a lifeline. It exists every single day of your life, for every human on this planet. It’s how we do everything that we do. There’s no such thing as teaching your child too late but you’ve got to do it at some point.

Alexa von Tobel is the founder and Managing Partner of Inspired Capital.

We give our daughter an allowance for above and beyond chores. The other night she cleaned up and took the trash down the hall, which is above and beyond for a 4.5-year-old. So I said, "You just earned a dime and a quarter." And what was so cute was she asked if we could make a piggy bank just for her chore money. So I decided we would make a new piggy bank and let her decorate it that weekend. You want to lean on what your child gets excited about. Try to make it fun for them to learn the basics. Make it fun for them when you spend it. Make it fun when you exhaust the piggy bank. That’s when we’re going to take her to the bank and let her physically see the money and buy something and continue to connect those dots.

Fake It 'Til You Make It

With math, that is. Tremendous studies show that the way parents talk about math is so important. If parents say, "Ugh, I was never good at math, I didn’t like it,” their children will follow suit. You have to fake it 'til you make it because if children are led to believe that these basics are hard, then you are teaching them that it’s hard, that it’s supposed to be hard. But math is not that hard. The basics are not hard. Money is not hard. If you tell your children, "Mommy loves dealing with money, money is so interesting," you totally reorient the way that they think about learning it themselves.

It’s Never Too Late

Money is a lifeline. It exists every single day of your life, for every human on this planet. It’s how we do everything that we do. There’s no such thing as teaching your child too late but you’ve got to do it at some point.

Alexa von Tobel is the founder and Managing Partner of Inspired Capital.